Art by Matthew Fleming.

This episode was written and produced by Casey Emmerling.

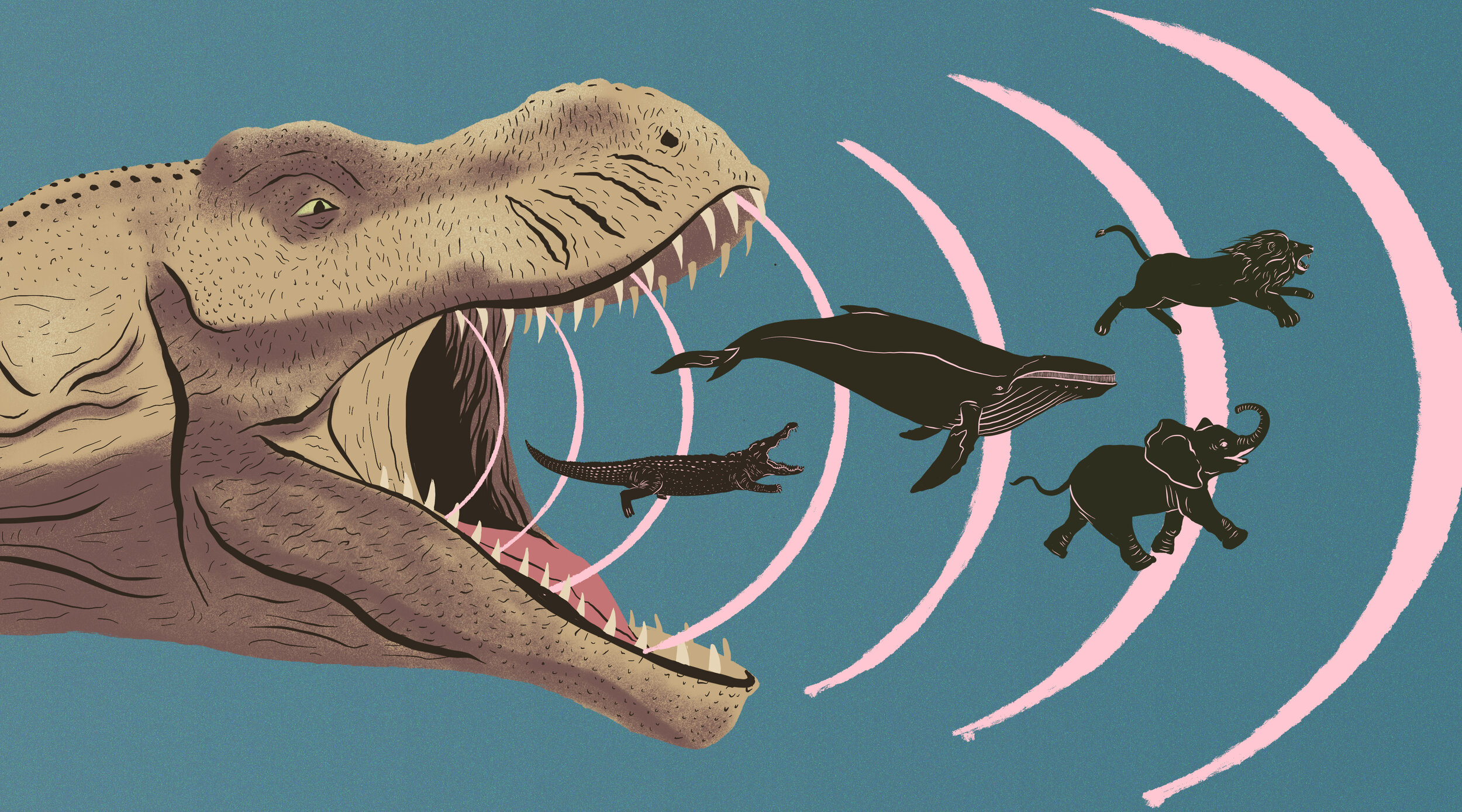

Technology has the power to transform the way our world sounds. It could even give us entirely new ways to experience our surroundings. In this episode, we explore the sounds of the future, and how we can use the tools we already have to build a better sounding world. Featuring Rose Eveleth, Creator and Host of the podcast Flash Forward, Acoustician Andrew Pyzdek, and Architect Chris Downey.

MUSIC FEATURED IN THIS EPISODE

Wanderer by Makeup and Vanity Set

1:57 AM (The Green Kingdom Remix) by Hotel Neon

Wide Eyed Wonder by Dustin Lau

June by Uncle Skeleton

Rubber Robot by Sound of Picture

Lick Stick by Nursery

Stuck Dream by Sound of Picture

Springtime by Sound of Picture

Drawing Mazes by Sound of Picture

Dark Matter by Sound of Picture

Brackish Water by Alistair Sung

About You (No Oohs and Ahs) by Vesky

Trek by Sound of Picture

Gimme Gimme - Instrumental by Johnny Stimson

Twenty Thousand Hertz is produced out of the studios of Defacto Sound and hosted by Dallas Taylor.

Follow Dallas on Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and LinkedIn.

Join our community on Reddit and follow us on Facebook.

Become a monthly contributor at 20k.org/donate.

If you know what this week's mystery sound is, tell us at mystery.20k.org.

To get your 20K referral link and earn rewards, visit 20k.org/refer.

Discover more at lexus.com/curiosity.

Subscribe to Flash Forward wherever you get your podcasts.

View Transcript ▶︎

You’re listening to Twenty Thousand Hertz. I’m Dallas Taylor.

[music in]

In our busy modern lives, it’s not often that we stop and really think about what we hear.

[SFX: Alarm, car start, city ambience, train, office ambience]

Most of the time, we just accept these human-made sounds without a second thought. But it’s important to remember that our world didn’t always sound this way. Matter of fact, the sound of our world changes constantly. Our cities and towns sound completely different now than they did fifty or a hundred years ago.

[SFX: Horse, old timey, car horn, klaxon, car pass by]

So what will our cities and towns sound like fifty… or even a hundred years from now? What if we could collectively sound design our world? What would that sonic utopia be like, and how can we get there?

[music out]

In our future sonic utopia, there will certainly be sounds we want to remove.

Rose: The first thing that comes to mind is the screech of the New York City subway, [SFX] which is incredibly loud and is sort of emblematic of the lack of updating of that city's infrastructure.

That’s Rose Eveleth.

Rose: I'm the creator and host of a podcast called Flash Forward, which is all about the future.

[music in]

[SFX: Subway train screeching as Rose describes it]

Rose: I love New York. But standing on the one train platform and the train rolls in [SFX] and you really feel like you're being stabbed in the ear.

We all know that loud noises can cause hearing loss, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. When we’re exposed to loud noise, our bodies release stress hormones. These hormones raise our blood pressure, which contributes to heart disease and Type 2 diabetes. Studies have even shown that kids who go to school in louder areas tend to have more behavioral problems, and also tend to skew worse on tests.

Rose: We know that constant sound like that has real impacts on learning, on people's ability to retain information.

[music out]

To be clear, this train problem goes way beyond the New York City subway. Anytime you have a heavy metal object moving along a metal track, like a subway, or a train, you’re probably going to end up with some screeching. But what if, in the future, that subway or train car wasn’t even touching the track?

[music in]

In recent years, some countries have begun building “maglev” trains, which is short for “magnetic levitation.” A maglev train doesn’t have a conventional engine. Instead, it uses powerful electromagnets to stay suspended above the track.

[SFX: Maglev train]

When it’s suspended, another set of magnets propel it forward.

Andrew: They don't have rails that they're rolling along physically.

That’s acoustician Andew Pyzdek.

Andrew: They're basically floating on a cushion of air, so they can be very, very quiet.

Maglev trains aren’t just quieter than normal ones, they’re also smoother and faster. The highest speed recorded on a maglev train was 373 miles an hour.4 As maglev trains replace normal ones, we can expect to hear less of this [SFX: Normal train] and more of this [SFX: Fast maglev].

[music out]

That’s a great start, but what about cars? As you may already know, electric cars can be extremely quiet. [SFX: Low-speed electric car]

Andrew: Obviously they're quieter, but most importantly at low speeds where the engine noise is the loudest thing.

As electric vehicles become more common, areas with low-speed traffic will quiet down quite a bit. But once you get on the freeway, even an electric engine doesn’t help that much.

Andrew: At high speeds on the freeway, most of the noise actually comes from the tires. [SFX: Car pass by] So the advancements that you can expect to improve roadway noise are… with the composition of the roads themselves.

In 2007, researchers developed a new paving method called Next Generation Concrete Surfaces.2 Roads that are paved this way are up to 10 decibels quieter than normal ones. That’s the difference between this [SFX: Busy freeway] and this [SFX: Busy freeway by -10bd quieter].

Andrew: As we improve infrastructure and replace old roads with new roads that are made to be quieter, we can see those freeways becoming less noisy.

[music in]

When it comes to transportation, our sonic utopia is sounding a lot quieter. But of course, people aren’t the only things being carried around in cars and trains. There’s also all of our stuff. Amazon currently ships over 6 million packages a day.6 As populations increase and countries develop, there will be an even bigger demand for quick delivery. And the latest idea to handle that demand is delivery by drone.

[music out]

Now, commercial drone delivery hasn’t taken off quite yet, but both Google and Amazon are working on changing that. Here’s a clip from a video that was made by Amazon:

[SFX Clip: “Amazon: Here’s how it works: Moments after receiving the order, an electrically powered Amazon drone makes its way down an automated track, and then rises into the sky with the customer’s package on board. Cruising quietly below 400 feet, carrying packages up to 5 pounds…”]

Amazon describes these drones as “quiet,” but in their videos, they never include the actual audio of flying drones. That’s probably because drones really aren’t that quiet. Even the small ones that hobbyists buy can be pretty loud. [SFX: drone]

If drone delivery becomes common, things could get really loud, really fast. Imagine a crowded city with hundreds of delivery drones buzzing by at all times. [SFX: Sparse drones]

Now imagine how bad it would be near the fulfillment center, where the drones actually take off and land. [SFX: Heavy drones]

This is not very utopian. But, thanks to nature, there may be ways of making drones quieter.

Andrew: There's some work that's been done looking at owls and the way that their feathers are shaped in order to reduce noise. So the edge of an owl's feather is very ragged. The feathers themselves are kind of loose and wavy. And that's why they're such stealthy fliers because their feathers aren't rigid.

For instance, barn owls fly so quietly that humans can’t hear them until they’re about 3 feet away.

Andrew: The exact opposite of that is a pigeon. And every time they take off, that pigeon sound, [SFX: Pigeon] some people think that it's a vocalization that the pigeons are making. That's the sound of their feathers vibrating as they flap their wings.

The recording of the pigeon you just heard is from a BBC special about owls. In the special, they recorded a pigeon, a hawk and an owl flying over a set of microphones. Here’s the pigeon again: [SFX: Pigeon] Here’s the hawk: [SFX: Hawk] And here’s the owl: [SFX: Owl]

Did you catch that? Neither did I. Here it is again, turned up twice as loud: [SFX: Owl]

Inspired by owls, researchers are already exploring ways of making airplanes quieter.

[SFX: Airplane]

Like a car on a freeway, a lot of the noise from a passing plane comes from air flowing around the plane. One way of reducing that noise would be to make the plane’s wings more like owls’ wings. This could be done by adding more flexible, porous materials to the edges of the wings. Theoretically, something similar might be possible with drones.

Andrew: I think that if drones start being a more everyday part of our lives, that there will be a pretty strong pressure to make those drones be a little bit less annoying to listen to. [music in]

So far, we’ve turned down the volume on future cars, trains, planes and drones. Not too shabby. But what does our sonic future sound like if you’re getting around on foot? Something that might become common is targeted audio messages that you can hear as you walk down the street. When audio is beamed to a small, specific area, it’s called an “acoustic spotlight.” These are already found in many museums.

Andrew: Say if you were looking at a painting, you might hear sounds that remind you of the space and the painting.

For instance, you may walk up to a painting of a peaceful landscape, and hear this

[music out]

[SFX: birds, light wind, blowing grass].

Andrew: And the technologies that are used to make these acoustic spotlights can range from very simple: There's parabolic microphones, where you have just a plastic shell around a normal speaker. And as that speaker generates sound, it focuses it downwards towards the person standing under the spotlight.

But acoustic spotlights can also be made with ultrasound.

[music in]

Andrew: Ultrasound is very amazing. Ultrasound is sound. It's not something different. It's just sound that's at a frequency above what people can hear.

The normal range of human hearing is from about twenty hertz to twenty thousand hertz [SFX: Sine wave of 20 hertz sliding up to 20,000 hertz]. Anything above 20,000 hertz is considered ultrasound. Making an acoustic spotlight with ultrasound involves something called a “parametric array.”

Andrew: So parametric arrays are basically you have two beams of ultrasound that you make intersect with each other. And at the point where they intersect, they create audible sound.

[music out]

A parametric array is almost like a sonic laser that lets you beam a sound message to a very precise spot [SFX: VO shifting around like it’s looking for a target]. If advertisers started doing this, it could get out of hand pretty quickly. Imagine you’re walking downtown in a crowded city. [SFX: Times Square ambience]

Every time you pass by a billboard or a store or a restaurant, you hear a little commercial or jingle. [SFX: Walmart] [SFX: McDonalds] [SFX: New in theaters] [SFX: Parasitic infection] [SFX: Pringles]

That’s definitely not what I want in my utopia. But audio aimed at your location doesn’t have to be a bad thing. For instance, rather than just playing the sound out in the open, the signals could be beamed to a device, like a specialized headset. That way, you could choose whether or not to tune in.

[music in]

Rose: I think in my utopia people would be able to kind of customize their experience to themselves. I could make the world feel safe and happy and lovely wherever I am and that might look different from somebody else. And I don't know if that means special things that go in my ear that kind of like filter in and out the sounds that are important or not. Or whether that means high-tech technology that only beams aural information to certain people who have their profile set up to be like maximum sound versus minimum sound, or whatever it is.

Rose: And you can kind of choose to customize your experience of the world that way.

In the future, headphones and earbuds won’t just be headphones and earbuds. They’ll be much more integrated. We already have noise reduction, but future hearing wearables may have selective noise reduction. They may filter out unpleasant sounds, or reduce dangerous volume levels. They may even have corrective hearing loss algorithms built in… like a merger of current hearing aids, noise protection, and traditional earbuds.

[music out]

With geolocation targeting, these headsets could give you extra information about your surroundings, without the visual distraction of smart glasses. Imagine kind of an audio tour of the entire world. This might even help people build more of a connection with their community.

[music in]

Rose: I think that there is a space for like, a sort of community audio project where you could have this living audio document that is kind of like a museum tour, but for your own space.

Rose: So you could be walking down your street and you could hear a story from your neighbor about something.

Rose: It's maybe the person who's lived on that block for 30 years being like, "You might not know this, but here's an interesting piece of history about where you're from." Or, you know "Hey, there's a city council meeting today. Maybe consider going to it."

Rose: Just little things like that where you could constantly be keeping up with your neighbors or understanding what the needs are in the community.

[music out]

A hightech headset that you wear all the time could also be a game-changer when it comes to real-time translation. If every word you hear gets instantly translated into your native language...

Andrew: People can talk to other people speaking a different language and not have that language barrier. There's already quite a bit of work happening there, and that will continue to move forward.

[music in]

New technology could positively change how our cities, neighborhoods, and homes sound. It could even give us entirely new ways to experience our surroundings. But we have to put in the time and effort if we actually want our future to sound better. To get some perspective, it’s helpful to talk to someone who really understands how important sound is to the spaces we design. Maybe someone like an architect… who’s also blind. That’s coming up, after the break.

[music out]

MIDROLL

[music in]

From acoustic spotlights to swarms of retail drones, there’s all kinds of technology that’s likely to affect the sound of our future. But as we build that future, we have to ask ourselves… What kind of sonic environments do we want to create?

The spaces we design should be acoustically functional. In other words, the acoustics of a building should support whatever goes on in that building. But it’s about more than just utility. We also want the places we spend time in to just sound good.

[music out]

That’s easier said than done, and too often, people just don’t think about it.

[music in]

Chris: Sound is so often just left to be accidental.

That’s Chris Downey.

Chris: I'm an architect located in Piedmont, California just outside of Oakland.

As far as architects go, Chris has a pretty unique background. In 2008, he was having some trouble seeing clearly. An MRI scan revealed a brain tumor right against his optic nerve. Fortunately, doctors were able to remove the tumor through surgery. But two days after the procedure, Chris’ vision started to fail. After three days, he was blind.

[music out]

Of course, adjusting to life without sight took time. But Chris didn’t let blindness stop him from doing what he loves. In fact, he says that losing his sight has actually been helpful to his understanding of architecture.

[music in]

Chris: Losing my sight, as an architect, has really benefited my work by really getting me back in touch with the human bodily experience of being in the space at any given moment in time.

Chris: The sound of the space. The acoustic soundscape of the architecture [SFX: footsteps] as you move through it dynamically, hearing it as you move through and really listening to the architecture.

The choices that are made when a building is designed have a massive impact on what it’s going to sound like. Sometimes, these choices are very deliberate, like the way concert halls are designed to amplify and enhance the sound of an orchestra.

[music out, SFX: Applause]

A lot of the time, though, it can be hard to predict exactly what a building is going to end up sounding like.

Chris: It's so hard to draw or model sound. How do you do that? As architects, we can't do that. If we talk with an acoustic engineer, they might be able to give us all sorts of scientific representations of things. But unless you're a highly trained acoustic engineer, it means nothing.

Most of the time, you won’t really know until the building is finished.

Chris: And then it’s built. It's really too late.

At that point, you might not be happy with the result. Maybe you’ve had the experience of trying to study in a library where every little noise echoes off the walls. [SFX: Library ambience with heavy verb]

One way to prevent this is to digitally emulate what a space might sound like, while it’s still being designed.

Chris: There's been a really interesting collaboration I've had with some acoustic designers that have a sound lab that they use to model sound. They use it really to anticipate and demonstrate the sound of a music hall or some other very, sort of, acoustically intentional space.

Using this technology, you can input the dimensions and other aspects of a building you’re designing. Then, the computer can emulate what a voice... [SFX: Voice with room verb] or an instrument... [SFX: Saxophone with same room verb] or a footstep… [SFX: Footstep with room verb] is going to sound like inside that space.

[SFX: Over Chris’ next line we hear those same sounds with evolving room verbs]

Chris: You can tune it. You can test it, just as we do visually with drawings and models and photorealistic computer-aided renderings and things, it's doing the same thing with sound.

Chris: We started working with that for me to anticipate the dynamics of sound as you move through a space, so they put my cane tapping inside the digital space [SFX: Cane tapping] and then we hear what it's like to hear the architecture as you move through, and anticipate that, so that I can really design intentionally

Acoustic modeling technology isn’t universal yet, but some designers have started taking acoustics more seriously.

[SFX: Noisy airport sounds]

Airports are notoriously noisy, and all of that noise can make traveling even more stressful than needs to be. But many airports have started installing noise absorbing materials to help keep people calm. The next time you’re in a new terminal that feels unusually quiet, look up at the ceiling. Oftentimes, you’ll see very unique looking tiles. These tiles can be subtle enough to fit right in with the architecture, and they make a huge difference in sound quality.

Unfortunately, though, when it comes to noise, restaurants are still way behind. We’ve all had the experience of being in a restaurant that’s just uncomfortably loud. [SFX: Crowded restaurant gradually getting louder; chatter, silverware clinking]

Chris: There are environments in restaurants that the soundscape becomes really problematic.

Since Chris is blind, he can’t read someone’s lips or pick up cues through their facial expressions.

Chris: So I'm absolutely dependent on the acoustic environment to communicate. And some of these environments are so loud, it's just so exhausting to try to hear, that within 15 minutes, I'm done. I'm exhausted. I’ve had enough. [SFX: Restaurant sounds out] And in sharing that with other people, people with hearing impairments, they have the same experience, and it could be because of a hearing aid that the sound is very different, and it becomes nauseating.

Accessibility laws and city codes are the reason we have helpful sounds at crosswalks, [SFX] and ramps for wheelchairs. And while the US government does regulate how much noise workers should be exposed to, those codes are rarely enforced in places like restaurants and shops.

Chris: Our codes don't really deal with that, so I think that there's some more wisdom and more research and development that needs to come into creating safe environments in places like that.

[music in]

We used to talk about second hand smoke in bars. Well, you know, what's that acoustic environment doing to the health of the people that work in those environments?

Whether it’s noisy restaurants or noisy freeways, it’s easy to imagine that a quieter future would be a better future.

Andrew: I think that we kind of want silence more than we get it. And that's really what it comes down to is that we live in a very loud world. [SFX: Loud city montage] Finding silence is very difficult unless you live in a place that's already pretty quiet. So I can understand why the focus on making the world sound better is to make the world sound less. Because it sometimes feels like there's just too much vying for our attention.

[music out]

If I had a giant audio board for the world, I’d pull the fader down on most of what’s human made. Our brains love the sound of nature, and it would be great to get competing sounds out of the way. However, that doesn’t mean that all human made sounds should be lost.

Chris: There's been a lot of effort going into sound masking, masking of the sound in an environment, which from the blind experience isn't necessarily a good thing, because in masking the environment, we're losing some of the necessary sound. We need to hear the environment.

For instance, making cars completely silent could be dangerous.

Rose: I mean, I think many people probably have the experience of almost being hit by a Prius in a parking lot because you didn't notice it there because it doesn't make any sounds.

Chris: I've experienced new electric buses that are so quiet it's hard to even know they're there. I've had one that pulled up right in front of me when I'm standing at the sidewalk, and I didn't hear it approach and I kind of sensed there was something in front of me, and I reached up to find there was a bus there just a couple inches in front of my face. [SFX: Bus pulls away] And that was terrifying. So in trying to remove sounds and make some of these things quiet, you have to be careful about maintaining some necessary sound for safety.

All of this can feel overwhelming, but there are things you can do to make your surroundings sound a little better. The first step is to really hear your environment. To do that, you’ll need to make it as quiet as possible.

[SFX: Subtle HVAC sounds]

Andrew: Try powering off your house. Go to the breaker, cut off the power. [SFX: Power down, HVAC off] Assuming that that's not going to damage anything, turn off any sensitive electronics first that might get hurt by a brownout. But you can flip the breaker and hear how different your house sounds when there's nothing on. And then when you turn those individual breakers on, you'll notice right away. [SFX: Click + fridge] "That's what my refrigerator sounds like." Or, [SFX: Click + AC] "Wow, I didn't realize our AC unit was that loud." You usually don't notice these things until they're gone and they come back.

[music in]

Most of us can’t just go buy a quiet new AC unit, but this can still be a good exercise to help you notice the sounds that you may have been ignoring. Maybe you can power down that video game system all the way, rather than leaving it in sleep mode with the fan running. Maybe it’s time to put some WD-40 on that squeaky closet door. Maybe you can find a tapestry to hang in your living room. Soft surfaces are a friend to good sounding environments.

Maybe you could also write a friendly email to that restaurant that you’d love to go back to, if it wasn’t quite so loud. Or maybe you can write a letter to your mayor, or your representatives, and tell them how the screeching bus brakes wake your whole building up at 6:30 in the morning. The point is, even a little sonic change goes a long way. And if enough people start doing this, our future will sound better.

Chris: Sound can affect us on a subliminal level and it can set a mood it can make us struggle. It can put us at ease. So, I think it's a sense that we really need to pay a lot more attention to, to really add to the quality of our living experience, in whatever setting we're in.

Andrew: There's a lot that can happen right now that would be possible if people just were willing to do it.

[music out]

[music in]

Twenty Thousand Hertz is hosted by me, Dallas Taylor, and produced out of the sound design studios of Defacto Sound. Find out more at defactosound.com.

This episode was written and produced by Casey Emmerling, and me, Dallas Taylor. With help from Sam Schneble. It was edited and sound designed by Soren Begin, Joel Boyter, and Colin DeVarney.

Special thanks to our guests: Rose Eveleth, Andrew Pyzdeck and Chris Downey. Rose’s podcast Flash Forward is one of my favorites, it’s all about the possible and not so possible futures. You should definitely go subscribe. You can also find articles by Andrew at acousticstoday.org. And you can learn more about Chris’ work at arch4blind.com. That’s A-R-C-H, the number 4, blind dot com.

If there’s a show topic that you are dying to hear, you can tell us in tons of different ways. My favorite way is by writing a review. In that review, tap 5 stars and then give us your show idea. And even if you don’t have a show idea… I’d love for you to give us a quick 5 star rating anyway. Finally, you can always get in touch on Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, or by writing hi@20k.org.

Thanks for listening.

[music out]