Art by Divya Tak.

This episode was written and produced by Marissa Flaxbart.

When writer Paige Towers moved to one of the loudest cities in the world, she found herself overcome with anxiety and depression. She came to realize that the noise of the city itself, and the inability to escape from it, was having a huge impact on her mental health. With the help of the internet, Paige was able to discover a deceptively simple solution. But the negative health implications of noise pollution are anything but simple.

MUSIC FEATURED IN THIS EPISODE

Odd Wand by Sound of Picture

Reelings by Sunshine Recorder

Always Infinity (with goosetaf & Fourth Dogma) by Kyle McEvoy

An Inside Battle by Benjamin Gustafsson

Intermezzo by Sound of Picture

Discovery by Makeup and Vanity Set

In the Shattering of Things by Hammock

Paper Feather by Migration

Twenty Thousand Hertz is produced out of the studios of Defacto Sound and hosted by Dallas Taylor.

Follow Dallas on Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and LinkedIn.

Join our community on Reddit and follow us on Facebook.

Become a monthly contributor at 20k.org/donate.

If you know what this week's mystery sound is, tell us at mystery.20k.org.

To get your 20K referral link and earn rewards, visit 20k.org/refer.

Check out Wireframe wherever you get your podcasts.

Apply to join the Defacto Sound team at apprentice.defactosound.com.

View Transcript ▶︎

[SFX: Forest river ambience]

Paige: I grew up in Iowa, I grew up in a really quiet place and a really quiet family.

[SFX: Forest river ambience continues]

Paige: So, I think that might be part of the reason why I am hypersensitive to noise.

This is Paige Towers. She grew up in the midwest, and her childhood was filled with the sounds of nature. When she played outside she was surrounded by birdsong and rustling leaves. But as she grew up, Paige’s path towards becoming a writer took her far from her peaceful comfort zone.

[SFX: Airplane and city ambience]

Paige: When I grew up and I started traveling the world, and living abroad, and living in these major US cities, that was exciting, and it's what I needed and wanted to do for my career. But it was kind of a shock to my nervous system because I just grew up in a place where you can go outside at night and you listen to cicadas… [SFX: quiet country ambience replaces city noise]… and wind in the trees, it's very quiet. ... and although noise bothered me when I was moving to all these cities... It really wasn't until later that all these things kind of caught up with me.

You’re listening to Twenty Thousand Hertz.

[music in]

Paige has written in places like the Washington Post and the Guardian about her struggles with noise. Living in some of the loudest cities on the planet taught her a lot about her own mental health…

Paige: I, as a very young kid, remember just being completely overwhelmed by noisy environments, [SFX: Amusement park ambience] except the fact that I was a young child, and I was not able to express, like, "Hey, I am over stimulated." Instead, I was just labeled difficult. I think that they knew that I was shy, introverted, but really, what was really triggering for me was like if I was in a mall, or at a carnival or something [SFX: Carnival ambience; merry-go-round music children shrieking] , it could be really fun for about an hour. Then, I just started to feel panicky. Like, "I have to get out of here. I have to go somewhere quiet. I have to reset."

[SFX: Music and design crescendos into a stylized stop, then music continues]

Paige: The noise has always felt to me almost like it had physical weight. I could feel it vibrating [SFX] in my bones. It felt like no matter what I did to just try to distract myself or stay calm, or whatever, I knew what I needed was quiet.

[music out]

[SFX: Return to nature ambience]

Paige: I got to walk home by myself, which was very quiet. I would take myself down to the park. I would trespass on people's farms. I would go to the woods.

Paige’s need for quiet often meant seeking solitude. So it was easily mistaken for social anxiety. She couldn’t quite figure out why she was so desperate to leave noisy places.

Paige: We inherently think people who like quiet are old, and crotchety, and just like the antithesis of fun. And so, I never was able to express or maybe even identify, like, "Hey, I need quiet." [SFX: Fade in party music/ambience] when I was in college, I would have fun at a party for a while or at a bar for a while, and then, I just sort of felt like ...what I realize now and I didn't even know then...I was kind of having symptoms of a panic attack. And if I could get myself outside, or even like to the bathroom and just relax for a little bit and just take in the quiet, then, I was fine.

[SFX: Cut party sounds/music]

[music in]

Paige: I need to go somewhere where I can feel like myself, and feel calm, and then, I could come back and then, I'd be fine. It's not that I didn't love hanging out with my friends, and I loved music, and I loved doing all of these things, it's just that I'm somebody who does not feel like myself unless I can escape to nature at least daily. I've moved to all of these different big cities, and what I realize now, I wasn't just seeking out nature because I like nature. I was seeking out quiet.

[music out]

It wasn’t until Paige landed in New York that she realized that her anxiety wasn’t about being around other people. Maybe it wasn’t even about being in nature. It was really about the constant weight of inescapable noise.

Paige: In every other place I lived before New York City...I always had an outlet. I lived in Seoul, South Korea for a while, that's a really loud city, but I could go walking along the Han River, [SFX: Park ambience] or I could go visit a Buddhist Temple. I lived in Denver, Colorado, you could take one-hour drive to the mountains [SFX: Cold wind]. I lived in Boston, and I lived in Roxbury, that neighborhood. [SFX: Dog bark] I would go walking through Franklin Park. It's really desolate, and really lovely, and quiet. I've lived in a lot of places but it was the first time when I moved to New York City, [SFX: Traffic white noise] that's when I discovered, like, not even in Central Park or on Randalls Island could I find a place that was at least even free of traffic noise.

[SFX: Traffic noise crescendos into music]

[music In]

Paige: So, when I moved to New York City, the first three months were super exciting. It's stimulating, it's chaotic, especially if you're from Iowa like me, you are walking around going like, "I made it. I'm here. I'm doing it." You can go to the museum, you go out for drinks. You could stay all night. It's great.

But after three months, Paige started to fall apart. She felt overwhelmed, frazzled, and she wasn’t sleeping well.

[music modulates eerily and fades out]

She needed a break from the constant noise… but the noise was everywhere.

[SFX: Traffic white noise]

Paige: If you place yourself on any street in Manhattan, there's always this underlying whoosh of traffic, which if you are sensitive to sound, you'll probably pick up on pretty quickly. I always view that as the underlayer, was the constant sound of traffic. Then, layering on top of that are all the more startling sounds, the louder sounds. Obviously, there are ambulance and police sirens. [SFX: Sirens]

Paige: New York City is just chronically under construction, so there's always just a jackhammer happening, [SFX: Jackhammer] that you're walking by. There's nail guns. [SFX: Nail gun. Hammers. Construction workers shouting] There's machinery. There's a lot of garbage in New York City, so there's a lot of garbage trucks, so there's the rumbling garbage trucks going by. [SFX: Garbage trucks beeping] There's a lot of buses, and buses have those air brakes which let off that really loud whooshing sound. [SFX: Bus screeching, beeping as it kneels] You'll see people's dogs always like jerking when they hear that sound, because it's just very alarming. Then, the closer you get to the east river or Hudson, there's factory noise. [SFX: Factory noise hum]

Paige: In the summer, there's always the hum of air conditioners. [SFX: Additional low hum] There's exhaust fans. There's honking cars, obviously. [SFX: Extra honks] Then, of course, there's music streaming out of the bars. [SFX: Bassy, muffled music] There's people talking. [SFX: chatter, laughter of passing people] People talking on speaker phone while they walk down the street. There's the subway screech, [SFX: Subway approaching, then stopping] which it's funny because everybody just sort of stands there and endures the sound of the subway approaching, which it's well over 100 decibels, and can cause hearing damage over time.

Many New Yorkers take pride in being able to handle the noise… but just because you can handle it, doesn't mean it can’t affect you.

Paige: If you look, you always see little children placing their hands over their ears whenever the subway is approaching, because they don't have an image to uphold. They don't have to be cool. They don't have look tough, and their body is saying, "Hey, that sound is really loud. You should probably cover your ears."

[SFX: End city noise]

Alright, take a deep breath [SFX: inhale, exhale]. That was a lot of noise you just had thrown at you. Luckily, it was only for a couple minutes and you could turn down the podcast if you needed to. But if you live in a place like New York City, that level of noise isn’t temporary and you can’t turn it down.

Paige: It's a great city and there's so many wonderful things about it: it's diverse, and it's artistic, and you can be yourself there, but I cringe when I think about some of those things. My shoulders get tight. This sounds dramatic, but I literally, some days, I was like, I feel like I'm going to die. Like, "I have to get out of here."

Paige’s experience may sound a bit extreme, especially if noise doesn’t bother you personally. But noise affects all of us, whether we realize it or not. Studies show that continued exposure to loud noise can increase blood pressure and affect our sleep… not to mention it's just plain stressful. It’s something that we all need an occasional escape from, but escaping isn’t possible for everyone.

Paige: If you don't have the money to go to The Hamptons, or the Catskills, or have a car, or anything like that, then, you can't escape it. You're stuck with it, and a lot of research has shown, it's the people that are stuck with it that are affected the most. Unfortunately, that makes for a lot of poor, a lot of minority neighborhoods that are dealing with the most noise, and they're the ones that can't leave.

[music in]

Paige: About three months in...it was like a Saturday morning where I woke up and my husband Kumar had left for work. I woke up around 6:00 and I was like, "What am I going to do today?" It hit me that I couldn't hear bird song even though the window was open. I put on my shoes and went to Central Park, that was like 6:30 a.m., and it was already filling up with tourists. There were sirens [SFX: Sirens] going by, people were playing music and there's this traffic noise. I still couldn't hear a bird song.

Paige: Usually, if I'm feeling anxious, or I'm feeling down, in the past it's always been, "Okay, I'm going to go into nature somewhere and I'm going to walk it off, I'm going to breathe, and in an hour or so, I'm going to be okay." But this was a thing where it was like the more I kept walking, the more overwhelmed I became, because the louder the city was becoming. And so, I had the classic symptoms of panic, where it was like my shoulders were super tensed. I was starting to get a terrible stress headache. My heart rate, I couldn't get it to calm down. I broke out into cold sweats, and I felt like screaming. I felt like I just needed everything to shut up for a while. I just wanted human-made noise, all of these artificial noises to go away for a little bit.

[music out]

Paige was finding it hard to focus on her work, and honestly, just to get through the day. The whole situation was becoming unsustainable for her. Finally, she decided to seek help.

Paige: So, when I first went to see a therapist in New York City, I had hit rock bottom. I was not doing well, so initially, we're addressing just depression and how I can get myself off the floor. Pretty quick we discovered, "Okay, what's the trigger for your anxiety? What's the trigger for you panicking? What's the trigger for you going into these downward depressive spirals?" I would start to talk about how on my commutes home from work, when I [SFX: Construction noise] was passing construction workers using jackhammers, I was just feeling extremely weak, and I was feeling like I had to cry. And so it sounds ridiculous, but I hadn't completely realized that that was what was happening, because I was so low in mood all the time, that I wasn't really aware that it was triggered by noise.

[music in]

Paige had reached her breaking point. But she was also about to discover a way to cope with the noise around her… by fighting sound with sound. Also, how do we fix the noise that our cities are so reliant on? All that, after this.

[music out]

MIDROLL

[music in]

Today, writer Paige Towers can look back and connect the dots between her noise sensitivity and her anxiety. That realization though didn’t come easily. Paige had to reach her lowest point before she realized noise was the problem.

[music out]

Paige: So, my therapist suggested that I put on headphones, it sounds simple, like I should have known to do that. ...putting on noise canceling headphones and walking around the city was really unnerving for me at first, because I just felt so vulnerable because I can't hear anything, and somebody's going to sneak up from behind. But that risk alone was worth every benefit I got from canceling out the noise, or from putting on headphones and listening to nature sounds while I'm walking through the city, because when I got home, I didn't collapse on the floor.

[SFX: Lake ambience]

Paige: The first ever nature sounds video that I Googled was the sound of a loon call, because I was born in Minnesota and lived there until I was six. And that was just one of my favorite sounds, was the sound of loon calls echoing over a lake in Minnesota. [SFX: Loon calls] I turned the sound of loons on as a way of masking, all the artificial noise, originally. Then, I just noticed how incredibly calm it made me.

This first little peek into nature sounds sent Paige down an internet rabbit hole. Turns out, there are a LOT of resources for piping the sounds of natural environments directly into our ears.

[SFX: Forest ambience]

Paige: I started looking at all these different sound videos on YouTube. There's one channel I love, it's called the Silent Watcher, it just has all of these videos, I think from Bulgaria, but they're in the forest. They're next to streams, and rivers, and it's the sound of bird song.

Paige: That would completely put me in a concentrated meditative state, which as a writer, obviously, I need to be in that state in order to sit there and create.

Paige: It just became a pattern of every morning I'd get up. I make my coffee. I walk my dogs. I do whatever. Then, as soon as I sit down at my laptop, the nature sounds come on, and I enter into a state of, I don't have to react to anything. I'm not in a fight or flight response. I'm just here in my natural state, and I'm going to work.

Paige: Since then, I have a pretty prolific collection of nature sounds...so, I use them not only as like a therapeutic tool, but also as a workspace tool.

[SFX: End forest ambience]

Paige had discovered a simple tool that anyone can use to combat stress. And that’s great. But the world outside our headphones just keeps getting louder, and evidence shows that anxiety is just one of the many negative effects of noise.

[music in]

Paige: There is an increasing amount of research on noise pollution and many cities are so chronically loud, again, particularly in poor minority areas, that residents experience elevated heart rates, they experience elevated blood pressure. There's higher incidences of stroke, and sleep disturbances, and cardiovascular disease. There's higher incidences of depression.

Paige: It was really reassuring, when I was experiencing this elevated heart rate, and cold sweats, and headache, and anxiety, and depression...it was wonderful to learn, "Okay, I'm not crazy. I'm not the only one. This is widely researched throughout the US, and Asia, and Europe." If you live in a place with just a high density of noise, that you're just so much more susceptible to a variety of health issues.

[music out]

Many people who live in noisy urban areas have been fighting to make their surroundings quieter. One of their main requests is to create more green space, like parks and gardens. Research shows that these changes can have a big positive health benefit, but there is still plenty of opposition.

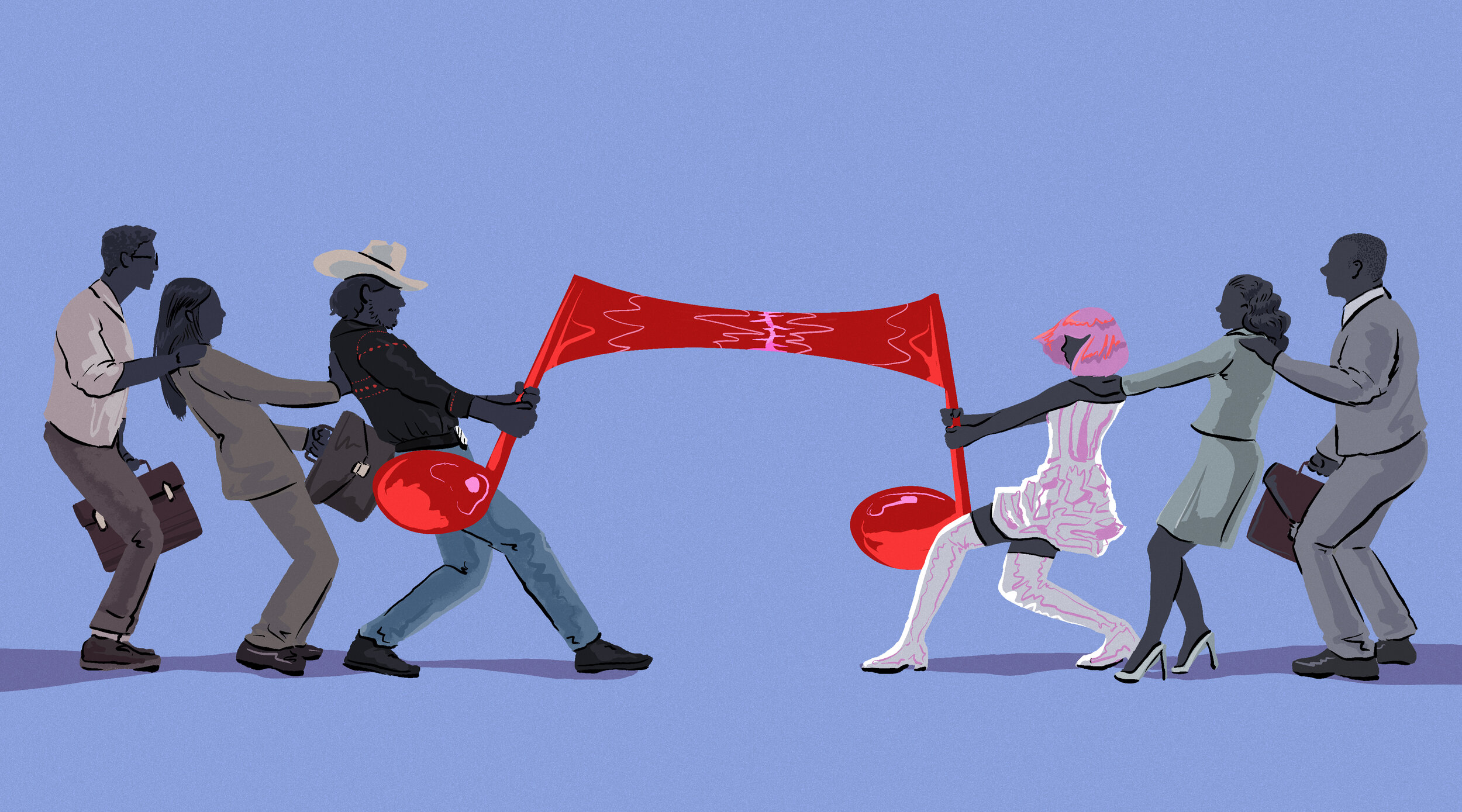

Paige: It's a hard thing to fight, not only because noise is invisible, but because noise is productivity. Noise is manufacturing. It's industry, and technology, and transportation. Noise is capitalism, noise is money. So, why would we want to change that? Especially if you have enough money and privilege, you can just escape the noise anyway by heading to The Hamptons for the weekend. So, there are a lot of anti-noise organizations out there doing amazing work, but they fight a hard battle.

These organizations aren’t just advocating for another park here and there. They want city officials to rethink how we treat noise from the ground up. It’s only then that we’ll see real progress. Now, the best time to fix these issues was years ago, but the next best time is now.

[music in]

Paige: It's sort of remarkable that we have allowed ourselves to get to this point where we are literally inundated with so much noise to the point where we have to talk really loud to be able to hear each other. We act as if this is just part of city living, you're like, "Suck it up." But in reality, it's insane. I don't know. I really do think that we're heading for a decibel breaking point, but that's just my opinion.

It’s my opinion too. Look around you: Unless you’re out in nature somewhere, I’m guessing most things in your vision were designed by people. The same goes for our senses of touch, taste, and smell. Think about it: if a fabric is uncomfortable to the touch, it doesn’t get made. If a food or drink has a bad taste, we avoid it. We’ve also done a lot to change how public spaces smell. Just a few decades ago, bars and restaurants were often filled with the smell of cigarette smoke. Now, laws have changed and that smell is much rarer in public spaces. That movement to stop people smoking indoors started with just a few persistent voices. Their concerns were dismissed, until more voices joined in. Then, research began to show the real negative effects of second-hand smoke, and finally the scales tipped. So why hasn’t this happened yet with noise yet?

Paige: On Twitter last year, there was some hashtag, that I’m not going to think of right now, where everybody was cleaning up litter, and they would show these before and after photos. Paige: That was wonderful, that's a great campaign, but it also is really easy because you can see the difference. It's right in front of your eyes.

But with sound and noise, we just don’t have that luxury.

[music fade out]

As a whole, we’ve simply accepted that our cities are really loud. The health implications of noise pollution have largely been ignored. There are things we can do in our own lives to limit noise, but Paige says that alone isn’t enough.

Paige: You can do a lot of things on your own. You can stop using a gas lawn mower. You can stop using a weed-whacker, and a leaf blower, and all these things, but ultimately, what's really the source of noise pollution is power. It's money. So, it's aircraft. It's military. It's oil drilling. It's factories. It's traffic and transportation. So, that takes a lot of collective action, but before we can get to the collective action, we have to have a lot more people on board. We have to have a lot more people thinking about, "Hey, how is all this noise around me affecting things?"

[music in]

Awareness is the first step towards change. Together we can make our world sound a little bit better. If you live in a noisy city, you can write your local representatives and tell them your concerns about noise. You can also support initiatives asking for more green space. Ask those in power to invest in structural changes that make our cities quieter. The good news is, human design can already offer real solutions. Buildings can be designed to act as noise shields... Better road surfaces can be used to limit traffic sounds... Cities can be designed to encourage more walking and biking. These are real changes that would make a world of difference to our society, and to us as individuals.

Paige: It just opens up this whole new world for you. You're not so inward focused. You're not ignoring the next person because you're just stressed. You're suddenly sort of hearing all these different things, and you're interacting with people. ...In the future, I would love to see everything taken down several notches. I think that we owe it to people to do that.

Paige: If I ever have kids, I do hope they look back at us all just sort driving around in cars and on motorcycles everywhere, and just all of this noise, all of this construction noise, everything, I hope they look back on it and be like, "Wow, that was crazy."

[music out]

[SFX: Return to nature sounds]

CREDITS

Twenty Thousand Hertz is produced out of the sound design studios of Defacto Sound. Find out more at defacto sound dot com.

This episode was written and produced by Marissa Flaxbart. And me, Dallas Taylor. With help from Sam Schneble. It was edited, sound designed, and mixed by Colin DeVarney.

Thanks so much to our guest, Paige Towers, for sharing her story and spreading awareness about our noise problem.

We could all use some anxiety relief right now. So for the next sixty seconds, we’re going to follow Paige’s advice and listen to the perfectly soothing sounds of the natural world. So take a moment to just let your mind calm and listen.

[SFX: Nature sounds continue for 1 minute]