Art by Jon McCormack.

This episode was written and produced by Leila Battison and Casey Emmerling.

When you imagine the sound of a dinosaur, you probably think of a scene from the Jurassic Park movies. How do sound designers make these extinct creatures sound so believably alive? And what does modern paleontology tell us about what dinosaurs REALLY sounded like? Featuring Jurassic World sound designer Al Nelson, and paleontologist Julia Clarke.

MUSIC FEATURED IN THIS EPISODE

Palms Down by Confectionery

Entwined Oddity by Bitters

Town Market by Onesuch Village

Coulis Coulis by Confectionery

The Poplar Grove by Bitters

Upon the Vine (Instrumental) by Graphite Man

Calisson by Clock Ticking

Beignet by Confectionary

Feisty and Tacky by Calumet

Contrarian by Sketchbook

Can't Stop Lovin You (Instrumental) by Brian Reith

Twenty Thousand Hertz is produced out of the studios of Defacto Sound and hosted by Dallas Taylor.

Follow Dallas on Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and LinkedIn.

Join our community on Reddit and follow us on Facebook.

Become a monthly contributor at 20k.org/donate.

If you know what this week's mystery sound is, tell us at mystery.20k.org.

To get your 20K referral link and earn rewards, visit 20k.org/refer.

Discover more at lexus.com/curiosity.

View Transcript ▶︎

You’re listening to Twenty Thousand Hertz.

[music in]

When Jurassic Park first came out, it brought dinosaurs to life in a way that people had never experienced before. Not only did the dinosaurs look incredible, but they also sounded amazing.

[SFX: Velociraptor Call]

Up until that point, there hadn’t been a clear idea in the public consciousness about what dinosaurs sounded like… so the filmmakers essentially had to make it up as they went along. To make these creatures sound believable and alive, they used all kinds of creative sound design techniques. The results are the stuff of sound design legend.

[music out]

Over the nearly thirty year history of the Jurassic Park franchise, the sound designers have faced one persistent challenge.

Al: How do you define the sound of an extinct animal that no one has actually ever heard for real and how do you make it convincing?

That’s Al Nelson, the lead sound designer on the new Jurassic World films.

[music in]

Al works at Skywalker Sound, which is the sound division of Lucasfilm.

Al: Where we're coming from, from the film sound standpoint is, is it believable? But is it also creating emotional context and is it helping the story?

Early in his career, Al worked with sound design superstars like Ben Burtt, the sound designer of Star Wars, as well as Gary Rydstrom and Chris Boyes, who made the sounds for the original Jurassic Park movies.

Al: That's where I got my real education and experience. There's this wonderful legacy at Skywalker of these brilliant icons with Ben and Gary.

Al: Then, there's this second generation of people like Chris Boyes and a handful of others. And then I was part of the third generation.

[music out]

Working at Skywalker Sound, Al got to see firsthand how some of the classic Jurassic Park sounds were made. To Al, there’s one sound that stands above all the rest.

[SFX: T-Rex Roar]

Al: The T-Rex is, in my opinion, one of the most iconic sounds in film sound history.

Now, it would be great if you could just go record a T-Rex in the wild, but of course, that’s not possible. So the original sound designers used a classic technique, and looked for inspiration elsewhere in the animal kingdom.

[music in]

Al: In those early days, they were out recording lots and lots of animals. Here, at one of the local theme parks, they had some elephants. And Chris Boyes was sent off to go record these elephants and out comes, trotting out a little baby elephant and it lets out one baby elephant roar [SFX: Baby elephant roar] and that was it.

Al: That iconic bellow, is the main ingredient of the T-Rex.

But creating that spine-tingling roar required other ingredients, too.

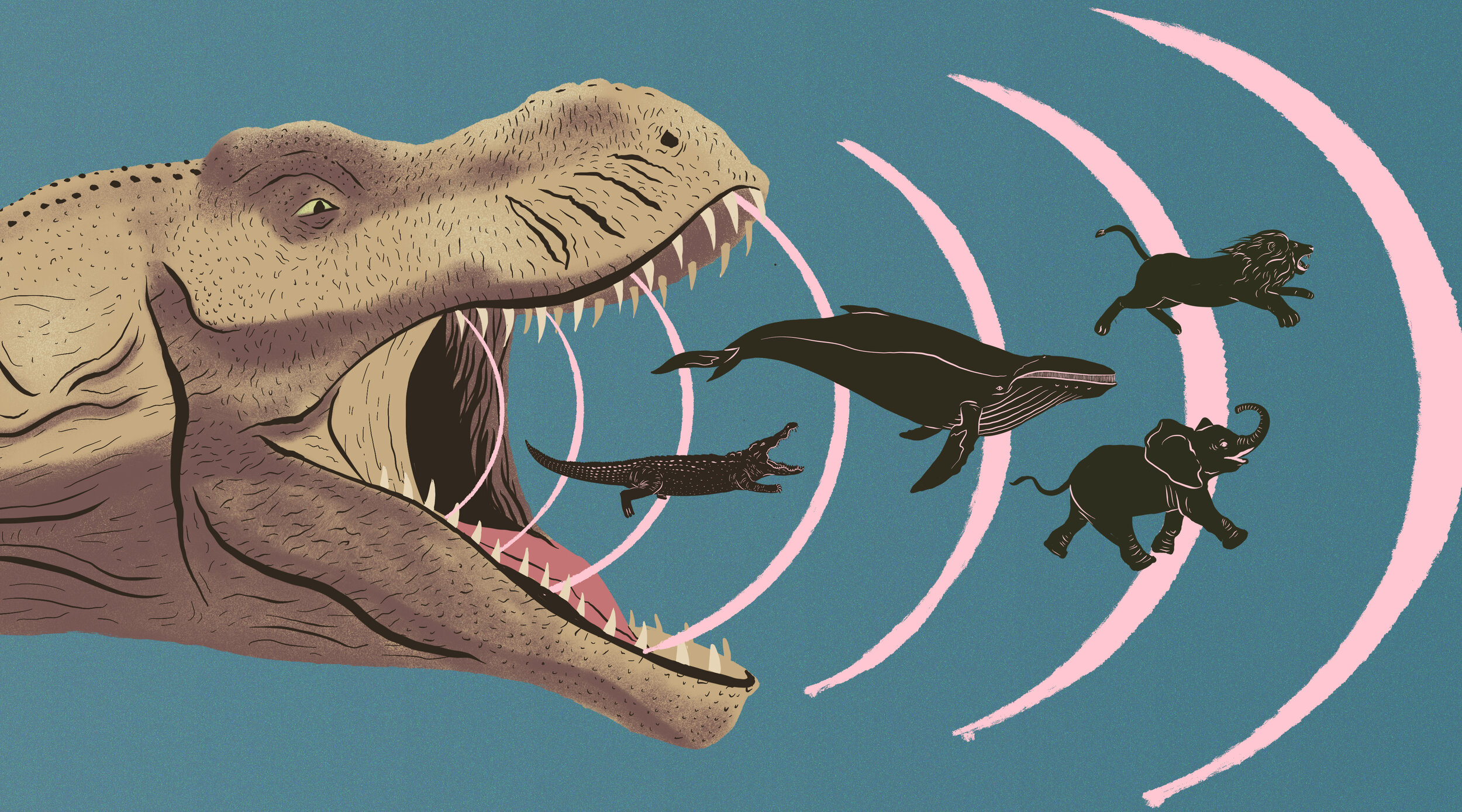

Al: He used some crocodile sounds [SFX: Crocodile rumble], lions [SFX: Lion SFX], the blow hole from a whale [SFX: Blow hole SFX].

Al: He knew just how to use that baby elephant [SFX] and just how to apply the deep grumble of the crocodile [SFX]or that raspy lion sound [SFX] at the beginning of it. And then, the blow hole sound [SFX] underneath the bellow to give it that weight.

Once these elements came together, [music fade out] the result was THE iconic dinosaur sound.

[T-Rex Roar SFX]

Of course, there are plenty of other dinosaurs in the Jurassic Park films, and all of them have their own unique voice. To make them, the sound team used a similar approach.

Al: You find these best little snippets of vocalizations, the sounds that have personality, and you figure out how to layer them.

For example, there was the gentle brachiosaurs—that’s the one with the long neck for eating leaves out of tall trees. To create their sound, the designers took hawing donkeys [SFX: Donkey SFX], and they slowed it down until it became a graceful song [SFX: Donkeys shift into brachiosaurus song].

There’s also a scene where the kids are caught in a stampede of dinosaurs that look sort of like ostriches. These are called gallimimus. To make their screeches, they used the frightening sound of a horse in heat [horse in heat].

That doesn’t sound quite like a gallimimus yet, but if we cut it up [SFX], bring up the pitch [SFX], then pan these sounds to the left and right [SFX], we can get pretty close to what we hear in the movie.

[SFX: gallimimus screech],

There’s also the predatory velociraptors [SFX: velociraptor SFX]. Their hunting calls were made using the sounds of dolphins [SFX: dolphin] as well as mating tortoises [SFX: mating tortoise].

These sounds are so convincing because the designers followed a few basic principles, based on the size of the creature, and its personality.

Al: We want to believe that those sounds belong in the body of that animal. Is it a Brachiosaur or is it a Compy?

For comparison, Brachiosaurs could grow up to 40 feet tall.

Al: If it's a big majestic dinosaur like the Brachiosaur you give it scale but you give it song.

[SFX Clip: Jurassic Park: They're singing]

While the compsognathus, or compy for short, was about the size of a chicken.

Al: With a Compy, it's a cute little dinosaur and then it gets aggressive. But in this case, you're choosing higher pitch sounds, bird sounds [SFX: birds] and even taking pitched up lions [SFX: lion] so that you don't have any more of that big weighted growl. You just have these unique squeaks and squeals.

[SFX: Compy squeaks]

In this way, the sound designers created an entire ecosystem of dinosaur sounds for the original movies. But when it was time to revisit these creatures in the new Jurassic World films, Al faced a unique challenge.

Al: We didn't want to break anything or modify anything that had already been heard and had already been created by Gary.

Al: I mean, you wouldn't ever want to mess with the T-Rex.

But there was a new creature in Jurassic World, a genetically-engineered mutant with an awesome name: the Indominus Rex.

Al: This was a dinosaur that was erratic and kind of broken. More of a screamer and more just unhinged.

To design this new sound, Al and his team went back to the drawing board.

[music in]

Al: Without any real idea of what specific animals I wanted to use, I and my team just started recording lots of new animals and animals that we knew hadn't been recorded previously.

Al: In particular, there was this little fennec fox, it's a desert fox.

Al: It just screamed and wailed and said everything it had to say at high pitches [SFX: Fennec fox screams]. So that was one of the ingredients. One of the reasons it was so useful is because it had that erratic screamy unhinged sound to it.

But just like the T-Rex, there were many layers to the Indominus sound...

Al: For some of the scale of the Indominus, we used very large sows, these huge pigs. At feeding time, the pigs get very aggressive and they bark and squeal [SFX: Sows squealing]. But they also growl at each other [SFX: boar growls] and they just, they sound like big mean animals.

Al: We had a howler monkey which was madly in love with his animal trainer. And when she sang to him, he would just go off into these long vocalizations as, “rar rar rar”. It was brilliant [SFX: Howler monkey song].

[music out]

When you mix the sounds of these animals just right, you get the Indominous Rex.

[SFX: Indominus roar]

Of course, Jurassic World also has dinosaurs from the original movies, like the velociraptors.

[SFX Clip: Jurassic Park: “Clever girl”]

But in the newer films, they got an update.

Al: We now get to experience the Raptors as not as passive but somewhat more trained and they work with their human handlers. And so they needed a new palette of gentler sounds and friendlier sounds.

Al and his team went in search of a new voice for these friendlier raptors.

Al: Ultimately, what we ended up using were mostly penguins, gentoo penguins [SFX: Gentoo penguins]. They do this shuttering and these softer cuter sounds that we were able to manipulate and make the Raptors more friendly [SFX: Friendly raptor noises].

But it wasn’t all elephants and penguins. Some dinosaur sounds were made with less-exotic animals. Gary Rydstrom, the original sound designer, snuck in a sample of his own.

[music in]

Al: One of Gary's traditions is to use his dogs for his animals.

Gary watched his Jack Russell terrier playing with a rope toy, and saw the similarity of the T-Rex grabbing and shaking other dinosaurs, and lawyers, to death. So he was inspired to use these sounds for the T-Rex. [SFX: Jack Russel Growls morph into T-rex shaking sounds]

For the newer films, Al decided to record his own dog.

Al: This was my opportunity to bring my black Labrador Bahama into the Jurassic sound palette. She does these sort of cute growls

[SFX: lab growl]

Al: They're not quite angry but they sound like, don't get too comfortable with me. So, whenever Owen would interact with the Raptors and they needed to check him, sometimes that would be one of the sounds we would use, is that cute low growl.

[SFX: Raptor growls]

[music out]

[music in]

It’s been almost thirty years since Jurassic Park was first released, and in that time, there’s been a lot of new developments in the field of paleontology. New research can tell us a lot about the what the Jurassic would have actually sounded like, and how that compares to what we hear in the movies. That’s coming up, after this.

[music out]

MIDROLL

[music in]

The dinosaurs of the Jurassic Park films aren’t just believable—They have personality and real emotion. One of the main reasons for this is the incredible sound design. But as with anything in Hollywood, sometimes scientific accuracy has to take a backseat to entertainment.

In the years since the original Jurassic Park, we’ve learned a lot about what dinosaurs probably looked and sounded like. To fill in the gaps between the movies and the real Jurassic world, we need a paleontologist.

[music out]

Julia: My name is Julia Clark and I'm a professor of paleontology at the University of Texas at Austin.

Julia: I have to say, the original Jurassic Park movie, it represented cutting edge science at the time, and that was exciting to see.

But Julia says certain parts of the movies just aren’t very realistic.

Julia: Oftentimes these dinosaurs in the movies are making really scary sounds as they're chasing prey items or children [SFX].

Julia: That's not a context in which most predators produce sound.

Imagine you’re a hungry tiger, creeping through the savanna.

[SFX: Savanna sfx, leaves rustling]

You spot your favourite snack, a lone antelope [SFX: Antelope], but it’s on the lookout, ears twitching for any sound that’s out of place. If you let out a blood-curdling roar [SFX: Roar], all you’re going to do is scare away your supper [SFX: Antelope running away]. There’s also a physiological reason why roaring and eating just don’t go together.

[music in]

Julia: if you were about to eat a cheeseburger, would you yell extremely loudly and then stuff the cheeseburger in your mouth? No, because those sounds that you're making are made on the exhale and now you've exhaled all the air out of your lungs and eaten a giant cheeseburger which is going to inhibit your ability to breathe in a second inhale potentially.

If you’re still not sure about this, give it a try at your next meal.

[SFX: Restaurant ambience, man yells, bite, gasp for air (meant to be ridiculous and all happens pretty quick]

Julia: I mean, when that T-Rex is chasing the small children, clearly the children are not a threat. It's not an aggressive display.

Julia: They would just be silent and about to eat them because you don't want to fully exhale with a loud sound [SFX: T-Rex Roar] and then have a giant bite of a child. [SFX: Bite]. It doesn't work.

But of course, it probably wouldn’t be very exciting if the T-Rex in Jurassic Park spent the whole movie creeping around silently.

[music out]

Al: My guess is that, if you're the T-Rex, you don't have to roar in reality. You just come up behind your prey and chomp down and that's that [SFX: sneak & chomp]. But we're watching these films and we want to inspire the kind of personality that the T-Rex has. It's scary. It's an aggressor, it's a carnivore.

And the sound design team wanted to give you that visceral experience right from the start. In Jurassic Park, the first glimpse of the T-Rex we get is when they pull up to its enclosure in the rain. They had tied up a goat to entice it, but now that goat is missing.

Al: It's completely quiet. There's nothing happening. There's no music, there's just a little bit of rain [SFX: rain]. And then you see the water start to ripple and you hear the distant thud. And you hear, "Where's the goat?" And if you just heard those thuds [SFX] and then the grumble [SFX] and that's it...there's something missing there. That dinosaur needs to present itself as dangerous. And so it slams its foot down [SFX], opens its mouth and gives out that iconic, blood curdling bellow [SFX]. So, that's cinema.

[music in]

So carnivorous dinosaurs probably didn’t roar while they hunted. But predators do roar to scare off threats and competitors. So when dinosaurs did make noise, what did they sound like? Julia studies dinosaurs’ closest living relatives—the reptiles—to figure out the kinds of sounds they could have made.

Julia: So reptiles include lizards and snakes, turtles, crocs and birds. Now a lot of people think, "What? You're putting birds in reptiles?" But if we think about a tree of life, that is the only sensical solution is that birds are really highly modified reptiles and they're really highly modified dinosaurs 9, 10

The period that came after the Jurassic is called the Cretaceous period. During that time, a new kind of feathered, flying dinosaur appeared. These were one of the only kinds of dinosaurs that survived the great extinction—when more familiar ones, like T. Rex, were wiped out.

Julia: All the birds that we have today, that's about 10,000 living species, they represent the descendants of one lineage of dinosaurs.13

[music out]

Julia’s research team noticed that modern birds and reptiles share a common vocal behaviour, called a closed-mouth vocalisation.

Julia: It sort of shapes the sound typically after it's produced in the vocal cords. A sound like, "Hmm, hmm," right, is a closed mouth sound.

Our own closed-mouth noises might be limited to a hum, but in other animals, with other body shapes, they can be really impressive.

[music in]

Julia: Crocodilians can make very loud sounds. Actually in crocodilians, some of the sounds that to us would sound most like a roar...they're kind of a rumble [SFX: Croc rumble]. Those rumbles are made with the mouth closed.

The birds we have now are sometimes called living dinosaurs, and they take closed-mouth vocalisations a step further.

Julia: Male ostriches have this boom call [SFX: Ostrich boom call] in which the mouth is closed and that's a very low frequency call [SFX: more ostrich boom calls].

Other birds make noises in a similar way. For instance, there’s the “coo” of a dove [SFX: dove cooing].

There’s the strange scooching sound of a bittern [SFX: bittern call].

And the weirdly-human call of the eider duck [SFX: eider duck call]

Julia: So what we think is that maybe some dinosaurs, maybe larger bodied dinosaurs, maybe they're using these closed mouth vocal behaviors ... like booming calls that they make to attract a mate or defend a territory.

Due to the sheer size of the largest dinosaurs, their booms would be much lower in pitch than even the largest birds. In fact, The sounds they made could have been so low that they’d be almost impossible for us humans to hear.

Julia: If we were around when T-Rex was around...we might feel these sounds of the largest dinosaurs more than we would hear them through our ears.

[music out]

These low rumbles weren’t the only type of sound you’d hear in the Jurassic. Some dinosaurs, known as Parasauralophus, had long skulls with tube-like holes, called vacuities inside them.

Julia: These vacuities don't produce sound, but they would shape sound.

Sound would bounce around inside these tubes, resonating and echoing almost like a didgeridoo.

[SFX: Low didgeridoo note]

In Jurassic Park 3, the resonating skull actually becomes a plot point.

Julia: they're trying to 3D print the vocal organ of a velociraptor and I guess the idea is that if they can communicate with these velociraptors they can influence their behavior.

[Jurassic Park 3 Clip: I give you the resonating chamber of a Velociraptor. Listen to this. [screech].]

Julia: I think it's really cool that at least in the Jurassic Park movies they were trying this out. That said, everything else about the science of that scene is kind of wrong.

Julia: So what they print they call a resonating chamber and a resonating chamber doesn't have the capacity to make sound. It would be something that shapes sound after it was produced.

Blowing into a resonating chamber without using your vocal cords wouldn't make any sound, just like blowing air down a didgeridoo would sound like this. [SFX: Hollow blowing sound]

In other words, the only way to make a real velociraptor sound is with a whole, living velociraptor.

If we put all of this together, we can start to get a more complete picture of the Jurassic soundscape. Julia thinks you may even be able to guess which geological period you were in, just by the sounds that you heard.

Julia: I think there's a lot of evolution of the sonic landscape throughout the age of extinct dinosaurs that we would hear. In earlier parts of dinosaur history where you have a lot of dinosaurs that are like, pony to horse size and bigger… those are going to be lower frequency sounds.

So the Jurassic period would have been a place of deep, bassy rumbles [SFX: Jurassic low-frequency soundscape]

Julia: It's only in the late Jurassic that we have evidence for things starting to take flight and smaller body sizes. By the time you get to the Cretaceous I think there's going to be a lot more higher frequency dinosaur sounds made by these smaller species.

Julia: It's still going to be a fairly foreign sonic landscape but there's still going to be some sounds that are almost bird like [SFX: Cretaceous soundscape under Julia]. It would be fascinating to be a dinosaur watcher in the Cretaceous.

[music in]

Figuring out the way the world sounded a hundred million years ago is hard work, but the drive to learn more keeps paleontologists like Julia going.

Julia: We start with simple curiosity, a question like… “How would we approach this? How would we figure out what dinosaurs sounded like?" That's a big question.

Julia: I feel so privileged to be able to be outside with a group of other scientists discovering new fossils but I also feel so privileged to work with all my students asking what might seem like kind of crazy questions and trying to figure out real ways of inquiry around those questions.

Maybe the next Jurassic film will represent dinosaurs in all their booming, cooing, rumbling glory. Whatever happens though, whether you’re in Hollywood or digging for dinosaur bones…

Al: There'll be lots of dino fun. I can promise you.

[music out]

[music in]

Twenty Thousand Hertz is hosted by me, Dallas Taylor, and produced out of the sound design studios of Defacto Sound. Hear more at defactosound.com.

This episode was written and produced by Leila Battison, and me Dallas Taylor, with help from Sam Schneble. It was story edited by Casey Emmerling. It was sound designed and mixed by Soren Begin and Jai Berger.

Thanks to our guests, Al Nelson, and Julia Clarke. You can find out more about Al at Skywalker sound dot com. And you can read about Julia’s research at julia clarke dash paleolab dot com.

Thanks to the Varmints podcast for helping us name this episode from Twitter. If you’d like to help name our episodes, help us with story directions, get sneak peeks of upcoming shows, or just want to tell us a cool sound fact… you can do that by following us on Facebook, Twitter, or our subreddit. And, if social isn’t your thing, you can drop us a note at hi at twenty kay dot org.

Thanks for listening.

[music out]