Art by Jon McCormack.

This episode was written and produced by Fil Corbitt.

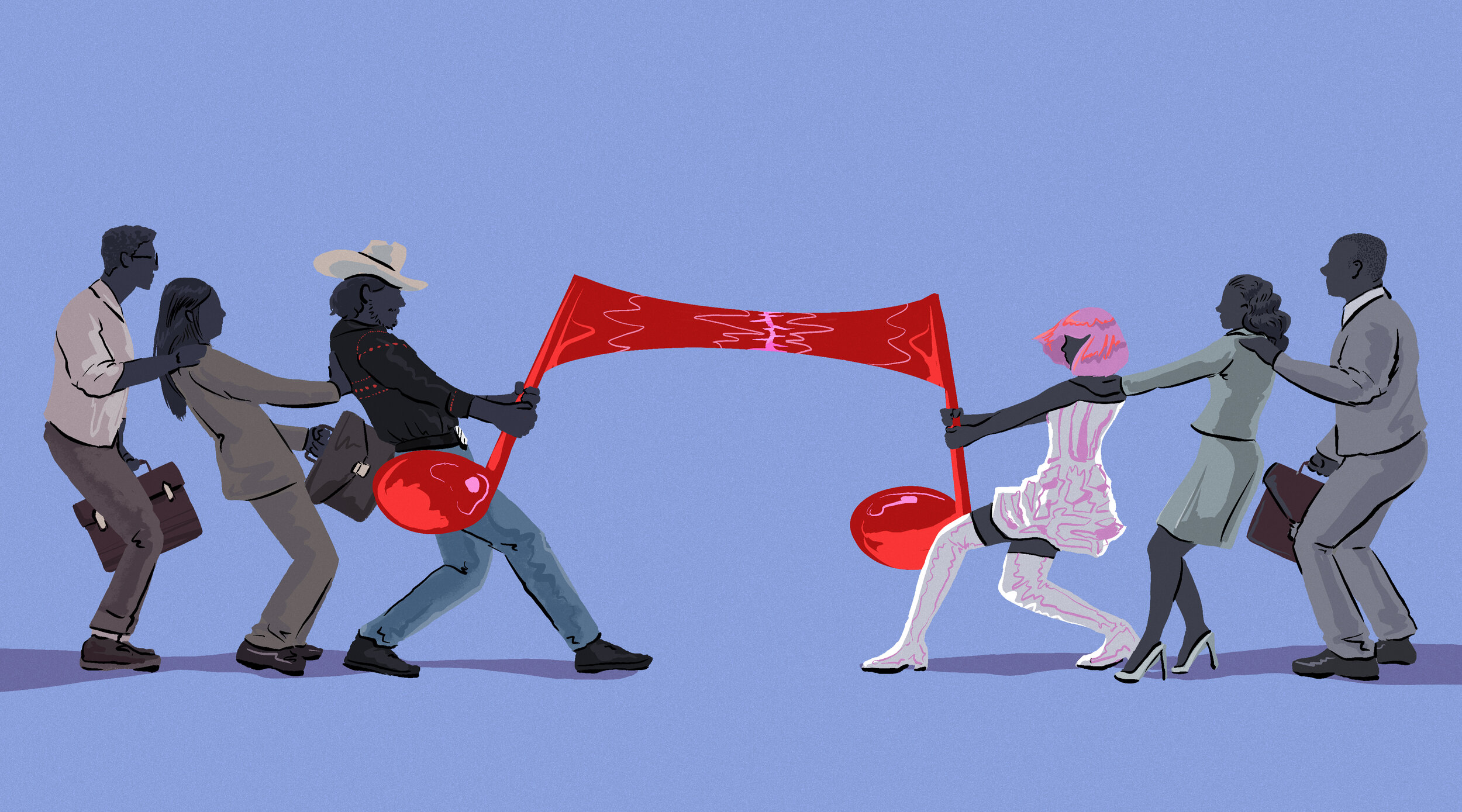

Most western music is built on the same 12 notes. Sometimes the arrangement of those notes sounds similar, which raises the question: Theft or Inspiration? We listen to some famous copyright disputes and try to decode them. Featuring Adam Neely and Sandra Aistars.

MUSIC FEATURED IN THIS EPISODE

Highride by Radiopink

A Path Unwinding by 4K

PlataZ by The Fence

Tarte Tatin by Confectionary

The Molerat by Little Rock

Moon Bicycle Theme by American Moon Bicycle

Slider by Grey River

Kid Kodi by Skittle

MUSIC DISCUSSED IN THIS EPISODE

This Land is Your Land by Woody Guthrie - TRO-Essex

Stay With Me by Sam Smith - Capitol Records

I Won't Back Down by Tom Petty - MCA Records

Creep by RadioHead - Parlophone, EMI Records

Get Free by Lana Del Rey - Interscope, Polydor

The Air That I Breathe by The Hollies - Epic Records

Thinking Out Loud by Ed Sheeran - Asylum, Atlantic Records

Let’s Get It On by Marvin Gaye Tamla Records

When the World's on Fire by The Carter Family - Epic Records, The Carter Family

Oh My Loving Brother - Gospel Hymn

Whole Lotta Love by Led Zeppelin - Atlantic Records

You Need Love by Muddy Waters - Chess Records

The Lemon Song by Led Zeppelin - Atlantic Records

The Killing Floor by Howlin' Wolf - Chess Records

Dazed and Confused by Led Zeppelin - Atlantic Records

Dazed and Confused by Jake Holmes - Tower Records

Dark Horse by Katy Perry - Capitol Records

Joyful Noise by Flame - Cross Movement

Moments in Love by Art of Noise - ZTT, Island Records

Twenty Thousand Hertz is produced by Defacto Sound.

Subscribe on YouTube to see our video series.

If you know what this week's mystery sound is, tell us at mystery.20k.org.

Support the show and get ad-free episodes at 20k.org/plus.

Follow Dallas on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

Join our community on Reddit.

Consolidate your credit card debt today and get an additional interest rate discount at lightstream.com/20k.

Check out SONOS at sonos.com.

Check out Adam’s Youtube channel.

View Transcript ▶︎

You're listening to Twenty Thousand Hertz.

[Music Clip: Woody Guthrie - This Land is Your Land]

This Land is Your Land is one of the most famous American folk songs ever written. It’s even been called the other national anthem...but this song, somehow, does not belong to you and me.

You can’t sing it on stage, or put it on a record or in a movie without paying someone to use it. The only way I can even play it is because of fair use - And this song has been enveloped in a growing national debate about copyright law.

[music in]

For thousands of years people have been making and sharing music. And for thousands of years, nobody really owned it. It just existed. But with the rise of our ability to sell music, the way we determine who owns it has changed dramatically.

Sandra: My name is Sandra Aistars.

Sandra’s a professor at George Mason University.

Sandra: And I teach a class here where we represent artists and entertainers on copyright and entertainment law issues.

To start with the very basics... copyright law is intended to protect authors of creative work.

Sandra: Whether those are musicians, or literary authors, or software programmers, visual authors...

To create work, you just have to record it or write it down. You don’t even necessarily have to sell it or market it to own the copyright.

Sandra: A lot of people don't realize that you don't need to go to a government entity and register for a copyright in order to own a copyright in your work. You as the author own the copyright in the work from the moments that it's set down in some sort of tangible medium.

[music out]

If you come up with a melody and lyrics in the shower [SFX: shower running, singing], and you record it on your phone, you own the copyright. If you post it online [SFX: mouse click], and some famous singer rips it off [SFX: crowd cheering, produced version of shower song], you could theoretically sue and legally co-own that song. That is, assuming you could afford to take it to court.

But since music is art, and art is confusing, it’s usually not that easy to tell what’s a rip off and what is just inspired by somebody else.

Sandra: Everybody understands that people are inspired by other people's works, maybe even unintentionally. They've got some earworm that shows up after they've been concentrating on composing something and it sneaks into the work totally unintentionally.

So is it inspiration or theft? That’s the basic question behind a copyright lawsuit.

One recent copyright dispute was the hit song Stay with Me by Sam Smith which came out in 2014. It goes like this:

[Music Clip: Sam Smith - Stay with Me]

The chorus uses the same melody as Won’t Back Down by Tom Petty.

[Music Clip: Tom Petty - Won’t Back Down]

Tom Petty’s publisher got in touch with Sam Smith, who listened to both and acknowledged the clear similarity -- they said it was a complete accident -- and that was it. Tom Petty was given co-songwriting credits, which means he’s also entitled to royalties.

Let’s hear them back to back one more time…

[Music Clip: Sam Smith - Stay with Me]

[Music Clip: Tom Petty - Won’t Back Down]

Tom Petty was quoted in Rolling Stone Magazine as saying, quote “I have never had any hard feelings towards Sam… Most times you catch it before the song gets out the door but in this case it got by.”

So this case was solved easily, both artists agreed on the result. And Like many of these cases, it was settled out of court, so we don’t have much information about it. But what we do know that it's not uncommon for cases to get a lot messier than this.

And unsurprisingly, many artists don’t like being accused of theft.

For example, in 2018 Lana Del Rey posted a tweet claiming that Radiohead was suing her for ownership of the song Get Free, alleging it was similar to their 1992 song Creep.

Here’s Creep by Radiohead:

[Music Clip: Radiohead - Creep]

And here’s Get Free by Lana Del Rey:

[Music Clip: Lana Del Rey - Get Free]

Lana Del Rey tweeted that Radiohead sued her looking for a hundred percent of the publishing rights. Radiohead’s publishers shot back, saying that in fact no lawsuit had been filed, but that they had been in talks with Lana Del Rey’s publisher about the similarities.

Musical copyright is split into two categories. First - “master rights” control how music is used in film or television, and who can use it. And second - “publishing rights” which protect the actual songwriting, music, and lyrics.

Radiohead and Lana Del Rey apparently settled, though neither side has said exactly what agreement they came to. These cases are rarely public. The only reason we know anything, is that Lana Del Rey performed it in Brazil later that year and said this:

[Live Clip: Lana Del Rey “I mean now that my lawsuit’s over I guess I can sing that song any time I want right?” ]

But here’s the twist… in 1992, after Creep was released, Radiohead was sued for plagiarizing Creep from an early 70’s song by the Hollies.

Here’s Radiohead Again:

[Music Clip: Radiohead - Creep]

And this is The Air that I Breathe by the Hollies:

[Music Clip: The Hollies - The Air that I Breathe]

In the early nineties, the two songwriters of The Hollies successfully sued Radiohead and are now credited as songwriters on Creep.

Every copyright claim has to be looked at case-by-case. And to actually make decisions about violations it’s important to zoom in and look at the elements that music is made of.

[music in]

Music is a shared language. So there are tons of parts of music that everybody owns.

Like, you can’t copyright a single musical note. In western music, there are only 12 of them [SFX]. So if somebody were to own the note G [SFX]... it would be almost impossible to write music. It’s a common form of expression, like a letter of the alphabet. So you can’t own it.

Non-ownable forms of expression exist in other media as well. In visual art, you can’t copyright a simple shape - like a circle or a square. And in literature you can’t copyright emotions.

You can take that idea pretty far too. For example - if you were to write a play where boy meets girl, but their families were in a blood feud, so they try to run away with eachother and it goes horribly wrong… that’d be fine. Even though that’s the same basic plot behind Romeo And Juliet.

Sandra: On the other hand, if someone were to copy a Shakespearian ballad from beginning to end, that would clearly be a copyright infringement.

[music out]

Basically, you can’t own things that are considered common. So in music, a 4/4 rock beat [SFX] or a simple bass line [SFX] are pretty common, and almost impossible to copyright.

Likewise - Many folk melodies include scales and even lyrical phrases that are simply too common to own. So when these cases go to court, each side has to prove if something is a “common expression”, or if it’s actually unique intellectual property.

[music in]

Sandra: The parties bring in musicologists that explain various subtleties of music composition, and try to help the jury understand which areas are protectable and which areas are not. Not surprisingly, the musicologist for the plaintiff will typically disagree with the musicologist for the defendant, and so you'll have two competing assertions of what's protectable and what's not protectable.

So in a hypothetical case like Radiohead vs. Lana Del Rey - Lana Del Rey’s lawyers would likely argue that the chord progression isn’t unique enough for Radiohead to own. Radiohead’s lawyers would argue the opposite. And, what’s surprising -- is that it would be up to a jury to decide. Not experts, but a regular old jury.

Sandra: Music is really an interesting area of the law here because we as listeners, audiences, we have our own ideas of what sounds similar, what doesn't sound similar…

So, a group of people who might not know anything about actually writing or playing music get to make the decision.

Sandra: The harder question is where to draw the line when you're talking about something that incorporates common types of musical expression.

And that line has been making some musicians very nervous.

[music out]

Adam: It leads to some pretty dark places, because if you can own one specific simple chord progression, you can own basically anything, and anybody can sue anybody else for any kind of little chord progression that is in any song.

This is Adam Neely.

Adam: I'm a bass player and also a music education YouTuber.

[music in]

Adam has a great youtube channel and has made a couple popular videos about music plagiarism. Adam says that recently the interpretation of copyright law has started finding plagiarism - but he thinks many of these cases should just be considered inspiration.

Adam: So historically, musicians have always built on what other musicians have done. We use the same scales, we use the same chord progressions, we use the same kinds of rhythms. And to say that you can own one of those elements in such a specific manner is just disingenuous to the entire art form and the entire craft.

In the last couple of years, there have been a few cases that have made huge waves in the world of songwriting. Cases that have changed the way we think of music ownership entirely.

We’ll talk about those cases, after the break.

[music out]

[MIDROLL]

[music in]

In the last couple of years, A few massive cases have rocked the world of songwriting. Contemporary pop stars have gone up against giants of music and unknown artists alike.

In 2018 Ed Sheeran was sued for the similarity between his song Thinking Out Loud and Marvin Gaye’s song “Let’s get it on.”

This lawsuit is mainly interesting because it isn’t about the melody, like most copyright cases.

Instead, this one is about the bassline, the chords and the drum grove.

[music out]

Here’s Thinking Out Loud by Ed Sheeran. Pay attention to the bass and drums.

[Music Clip: Ed Sheeran - Thinking out loud]

And Here’s Let’s get it On by Marvin Gaye:

[Music Clip: Marvin Gaye - Let’s Get It On]

So let’s dissect this - the bassline and drum groove are definitely similar. But the vocal melody is different, and the lyrics are different, the musical key is also different - but the chord progression is basically the same.

I’m going to layer these two songs on top of each other - Ed Sheran’s song has to be pitched up a little bit so they are in tune together. Listen to how the basic framework of the songs is the same, but all of the details in between are different…

[Music Clip: Ed Sheeran -layered with Marvin Gaye]

So the chords and the drum beat match. [Music fades to basic piano and drums] But neither Marvin Gaye or Ed Sheran invented these elements. The chords are a progression known as “one three four five”, and the drum beat is a basic rock drum pattern like you might learn in your first few drum lessons.

[music out]

[music in]

Marvin Gaye pretty much reshaped the way our culture sings about love. In many ways, what we think of as a smooth, romantic song can be attributed to his sensibilities. And it’s hard to create a contemporary romantic song without nodding to Marvin Gaye.

But inspiration isn’t illegal. And According to Adam, musicians have always built on what other musicians have done. So the context of what comes before gives new music part of its meaning. Adam argues that this is just a contemporary version of a very old musical concept called Cantus Firmus.

Adam: Cantus firmus was basically the technique of taking a melody that had already been written, and then writing other melodies on top of it.

Adam says this has been standard composition technique for hundreds of years.

[music out]

Adam: This is how Mozart learned how to compose. This is how Beethoven learned how to compose. Everybody learned to write by basically stealing other people's melodies and then writing other stuff on top of that.

And that’s not just for classical music. Think about folk songs. It was super common for people to learn songs from their parents or at church, add new verses and pass them on. Or, people would just take a melody they already knew and change the lyrics.

Which brings us back to Woody Guthrie’s This Land is your Land:

[Music Clip: Woody Guthrie - This Land is Your Land]

So that song that all of us know, simply repurposed a melody from The Carter Family. Here’s their song, “When the World’s on Fire”, from about 10 years before.

[Music Clip: When the World’s on Fire - The Carter Family]

Pretty similar, right? Well, the Carter Family didn’t make it up either. It was originally a Baptist gospel hymn called “Oh My Loving Brother”.

[Music Clip: Oh My Loving Brother]

The Carter Family even repurposed this same melody again for other songs. But none of this was unusual. These weren’t seen as plagiarism and the original songwriters were often anonymous or long, long gone.

[music in]

The first US Copyright Law passed in 1790. At that time, a copyright lasted 14 years, and you could renew it once. After that it was in the public domain, which means anybody could use it. Commercial, private, whatever. In 1909 Copyright was extended to 28 years, then extended again in 1976, and again in 1998. It keeps expanding.

So, when Woody Guthrie released This Land is Your Land, it wasn’t like copyright didn’t exist...people just treated music compositions differently, and a lot more of it was considered common expression. There were references to references to references -- an inception level of copyright violations in all types of music.

In fact, the note that Guthrie submitted with his copyright application read, quote “anybody caught singin it without our permission, will be mighty good friends of ourn, cause we don't give a dern. Publish it. Write it. Sing it. Swing to it. Yodel it. We wrote it, that's all we wanted to do” end quote.

[music out]

Keeping that in mind, in 2004, the comedy website JibJab posted a video with parody lyrics of the song.

[Music Clip: Jib Jab]

A company called The Richmond Organization claimed that they had purchased the copyright of This Land is Your Land, and threatened legal action.

To be proactive, JibJab sued first, claiming not only that parody was fair use, but that The Richmond Organization didn’t own it at all. Jib Jab won the parody part, but The Richmond Organization still claims ownership.

But how? If a song was copyrighted in the 1940s, and could only be held for 28 years, it seems like it should be in the public domain today.

[music in: Slider by Grey River]

By the mid 70s, copyright was extended to 70 years, OR the life of the author plus 50 years.

And THEN in the late 90s, that was extended to a whopping 120 years or the life of the author plus 70.

Just to reiterate that, what started as a law to protect a work for 14 years now will keep a work as private property for 120.

This is exactly how the Happy Birthday was held for so long. For years chain restaurants would sing some weird version of a birthday song…

[Music Clip: Applebees Happy Birthday]

And that was because the one we all know was protected by copyright, despite the fact that it was written sometime around 1912. The company that owned it was successfully sued recently and now anybody can use Happy Birthday for anything. Finally we can get rid of those uncomfortable happy birthday songs and get back to the real one.

After Happy Birthday was released into the public domain, This Land is Your Land came up in court again. It appeared as if it might be released. But….It wasn’t. The judge ruled that the Richmond Organization still retained ownership of the song, and it will not be in the public domain anytime soon.

Adam: The idea behind intellectual property is the protection of the artist, and as an artist and as a musician and talking to people around me, nobody feels protected by this. The only people who feel protected by this are the estates of pop artists who have passed.

On the other hand, Woody Guthrie’s daughter Nora, told the New York Times that this isn’t about the money, it’s about protecting the song from abuse and political use.

[music out]

Copyright is meant to allow artists to create work -and legally own it. Then you can prevent other people from stealing it and claiming it as their own. And that makes sense, because who wouldn’t want their work to help support their family - even after they’re gone.

This brings us to Led Zeppelin. Led Zeppelin was notorious for brazenly (ahem) borrowing from other songs. There’s even a wikipedia page called “Led Zeppelin songs written or inspired by others.”

Here’s Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love from 1969:

[Music Clip: Led Zeppelin - Whole Lotta Love]

And here is You Need Love by Willie Dixon, sung by Muddy Waters from 6 years earlier.

[Music Clip: Muddy Waters - You Need Love]

Here is The Lemon Song by Led Zeppelin:

[Music Clip: Led Zeppelin - Lemon Song]

And Here’s Killing Floor by Howlin’ Wolf:

[Music Clip: Howlin’ Wolf - Killing Floor]

Covering songs or attributing parts of a song are normal...but Led Zeppelin released these as their own, with themselves listed as the sole songwriters. They had actually even covered that Howlin’ Wolf song before, but when they released Lemon Song, they didn’t credit him, until they were sued and forced to.

Here’s “Dazed and Confused” by Led Zeppelin:

[Music clip: Led Zeppelin - Dazed and Confused]

And here’s “Dazed and Confused” from a few years earlier by Jake Holmes:

[Music Clip: Jake Holmes - Dazed and Confused]

On this one, Led Zeppelin didn’t even bother to change the name, and this song was originally credited just to Led Zeppelin. It was later changed to “inspired by Jake Holmes” and settled out of court.

Many of the world’s most famous musicians, from Bach to BB King, embrace the practice of borrowing bass lines, melodies and drum beats. But when does it cross the line from borrowing to outright stealing?

Some argue that this line is starting to move toward finding infringement too freely. In 2019, Katy Perry lost a lawsuit to the Christian rapper Flame. A jury found that her song Dark Horse featured an element that was too similar to Flame’s song Joyful Noise.

Here's the beginning of Katy Perry’s Dark Horse:

[Music Clip: Katy Perry - Dark Horse]

Here is the beginning of Flame’s Joyful Noise:

[Music Clip: Flame - Joyful Noise]

The similarity wasn’t the melody, or a lyric or a beat -- it was something called an Ostinato -- a repeated musical phrase, which in this case was a short synthesizer line.

Here’s Adam Neely’s youtube video Demonstrating Flame’s ostinato in Joyful Noise:

[SFX: Adam Neely Demo

“It Sounds like this:”

[music]

“Dark Horse’s Ostinato sounds suspiciously similar…(cut transpose line)”

[music]

“Oh wait I’m sorry, that’s actually not the Katy Perry -- that’s the adagio from Bach’s Violin sonata in F Minor. This is Katy Perry’s Dark Horse.”

[music]

“Wait sorry got confused again, that’s the traditional Christmas Carol Jolly Old St. Nicolas. THIS actually is the Katy Perry.”

[music]

“So the question is, is this similar enough to Joyful Noise to legally be the same piece of music? The jury seems to have ruled that IS the case.”]

In these examples Adam plays these notes on a synthesizer that sounds like the Katy Perry and Flame songs.

So theoretically you could argue that it’s not just the notes, but it’s also the presentation of the notes -- in this case an airy sounding synth instrument.

With that in mind, here is a song from the early 80s called Moments in Love, by the band Art of Noise:

[Music Clip: Art of Noise - Moments in Love]

Clearly, Flame was not the first person to play a minor key Ostinato like this in music. But, the case wasn’t about where Flame got the idea, it was whether Katy Perry had plagiarized it from Flame.

This ruling was actually reversed in 2020, in favor of Katy Perry. But Adam still worries these kinds of cases can paralyze creativity.

Adam: I really dislike the fact that this is being turned against people who are actually writing and creating music. Will I be protected? Will I be sued because I used a certain chord progression? Like what is the new law? I don't know.

And he says a lot of musicians feel confused and incredibly frustrated by the way this works.

Adam: So add onto that, the internet, and how remix culture and remixing of music has just exploded because of that, in meme culture and everywhere else. Copyright as a whole system just doesn't work the way that it's supposed to. It's supposed to protect people, but it doesn't. There are so few examples I can see of people genuinely needing copyright and genuinely relying upon copyright to protect them…

As if copyright and song ownership wasn’t complicated enough, hip hop in the 80s threw a whole new wrench in the gears with sampling.

We’ll deconstruct a whole new batch of cases - next time.

[music in]

Twenty Thousand Hertz is hosted by me, Dallas Taylor, and produced out of the studios of Defacto Sound, a sound design team dedicated to making television, film and games sound incredible. Find out more at defactosound.com.

This episode was produced by Fil Corbitt and me, Dallas Taylor, with help from Sam Schneble. It was sound designed and mixed by Soren Begin, and Nick Spradlin. The writer of this show, Fil Corbitt, is also the host of the fantastic podcast Van Sounds, a unique blend of music journalism, travel writing and experimental radio. You can find Van Sounds on apple podcasts or wherever you listen.

Thanks to our guests Sandra Aistars and Adam Neely for speaking with us. I am a huge, huge, huge fan of Adam Neely’s Youtube channel, and it was the Katy Perry / Flame video that made me want to do this entire episode.

Finally, what do you think about music copyright law? Do you think it stifles creativity, or do you think it protects an artist’s work without overreaching? Tell us what you think on Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, or by writing hi at 20k dot org.

Thanks for listening.

[music out]